Actor Prints and Kabuki, Inseparable

1/6/2016

By Paul Griffith

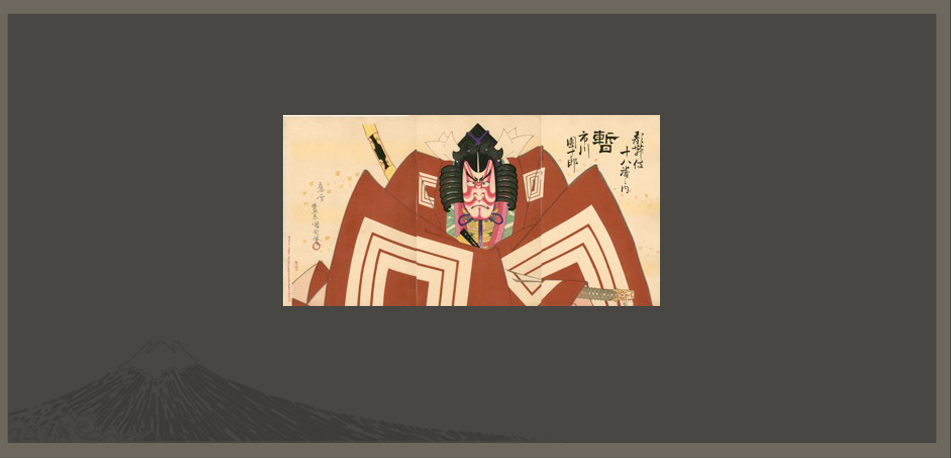

Yakusha-e

Kabuki actor portraits are called yakusha-e, literally ‘actor pictures,’ and they are one of the major subjects depicted in ukiyo-e. Yakusha-e artists were an integral part of Kabuki’s world, their works serving as vital publicity for the theatre. In turn, the theatre provided stories to illustrate and star actors to portray, as well as a ready market for the pictures among the theatre-going public.

Personal History

December, 2015, was a special anniversary for me. It marked exactly 30 years since I began working on English translations for the earphone guide service at the Kabuki-za and the National Theatre in Tokyo. The job has afforded me the privilege of attending countless performances of every kind of Kabuki play and dance, and has given me access to rehearsals, as well as to areas backstage, including the occasional visit to an actor’s dressing room. Above all, it has allowed me to get my hands on the working scripts. Learning to read these has been a challenging… sometimes painful… process that is still far from complete, but it has been one of the most fulfilling that I have experienced. At the Kabuki-za, the English earphone guide has now been replaced by English subtitles, allowing me to get even closer to the written texts.

Meanwhile, my association with ukiyo-e goes back even further. As a child I grew up with the handful of actor prints that my father had collected, and as soon as I hit my mid-teens I became interested in collecting myself. At first, I liked all ukiyo-e, but as my knowledge of the theatre deepened I came to specialize exclusively in yakusha-e. Over the years I have been fortunate enough to work on the yakusha-e collections in the Victoria and Albert Museum and, more recently, at the British Museum, where serious efforts are being made to record ever greater detail on their online database.

Today, the prints and the theatre are as one to me. They cannot be separated. It is easy to see where so many artists got their inspiration… they simply drew what they saw on stage. Kabuki is a theatre of great visual impact so that many of the poses are already ‘picture-like’. Furthermore, artists had to satisfy a very particular clientele in order to survive, and that was the Kabuki fan. Since one of the reasons for buying the prints was to ‘relive the moment,’ it follows that fans demanded that artists reproduce what they had just seen in the theatre. I feel exactly the same. Personally, I am less interested in star actors, or in portraiture itself as an art form. While, of course, I do appreciate the prints for their aesthetic appeal, what I also want from them is that feeling of excitement or heartache that I experienced from a particular moment on stage

What I hope to share in future posts here is this close connection between actor print and Kabuki performance. While many scripts have been lost, making it impossible to know exactly what is going on in some designs, there are a great many others that are still performed today. Hopefully, most of my posts will feel current. As I still translate for the Kabuki-za, I know all the forthcoming shows in advance and will try to pick subjects that one can actually go to see.

What is Kabuki?

The art of the Kabuki theatre has been at the forefront of Japanese popular culture for over four hundred years. Still very much alive and well, it now encompasses a huge variety of plays and dances typical of the eras and regions in which they were created. Though the main body of the repertoire comes from the 18th and 19th centuries, some works still performed may date back to the late 17th century, while others can be brand new.

Acting styles also vary, and just as there are older, highly stylised works performed with onstage musical accompaniment, so there are more recent dramas presented in a realistic way with either recorded music, or no music at all. Some works may be pure dance, others pure dialogue, or, as is commonly the case, a combination of the two.

In its essence though, Ka–bu–ki, (歌舞伎) written with the three characters that mean ‘song’, ‘dance’ and ‘acting skill’, is an art form combining very different disciplines that would in most other cases be performed separately.

Song / Music

Kabuki’s roots lie in musical theatre. This ranges from onstage accompaniment by singers, and players of drums, flutes and, most importantly, the three-stringed shamisen, to subtle offstage background music. There are four major schools of onstage musicians, each with their own distinctive singing style and sound. Kabuki actors of rank receive strict training in one or more forms of music from early youth and even if they do not need to sing or play instruments on stage, this background is considered essential to a proper understanding of the art. In the case of dances, of course, music, and especially song, is of vital importance.

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Vivamus leo ante, consectetur sit amet vulputate vel, dapibus sit amet lectus.

Often performed in gorgeous costumes against backdrops of great beauty, dances can be the most visually spectacular items on a Kabuki programme. Usually before the age of ten, and sometimes from as early as three, Kabuki actors study traditional Japanese dance called Nihon Buyō, and dances make up around one third of the existing repertoire. Kabuki, in fact, began as dance. The earliest records show that troupes of women entertainers in and around Kyoto put on revue-like shows featuring the performers dancing in a row. One particular troupe was led by a woman called Okuni, and it is she who is said to have founded Kabuki in 1603. But over the years, Kabuki and Kabuki dance evolved away from these primitive entertainments into a highly complex and sophisticated art.

A characteristic of most dances we see today is their specific dramatic content. Many were created as parts of longer plays, and in some way they reflect the stories of these plays in their subject-matter. Even when there is no particular story to tell, the dancer will still be ‘in character,’ portraying a wide variety of people from the refined princess to the humble street peddler. While the beauty of pure form and melody is also important, the existence of song lyrics ensures that there is also something for the dancer to enact. For this reason, there is a very close connection between dance and the literal meaning of the texts and Kabuki dance is never divorced from acting.

Acting Skill

Two thirds of the repertoire is made up not of dances but of plays, and every Kabuki actor is expected to perform both. Since the official banning of women from the stage for reasons of immorality in 1629, all roles in Kabuki have been played by men, and perhaps the most remarkable feature for the first-time spectator is the onnagata – the male actor who specialises in female roles.

In contrast to the onnagata, an actor who specialises in male roles is known as a tachiyaku. Within each gender category there are a number of standard role types, each with its own distinct acting conventions.For onnagata, important role types include the great courtesan of the red light district, the loyal samurai wife or the refined court lady, while for tachiyaku, important types may be the heroic warrior, the sinister villain or the gentle and romantic lover.

Kabuki Genres

Broadly speaking, traditional Kabuki plays fall into two categories, jidaimono (“history plays”) and sewamono(“domestic plays,”) although each of these categories includes several subdivisions, and a long play will often include acts in both the jidaimono and sewamono styles.

Jidaimono are set in an era predating the Edo Period (1603-1868) and they take as their main characters the members of the samurai aristocracy. Jidaimono history plays are often visually appealing with magnificent costumes, make-up and colourful sets. The acting techniques tend to be bold and stylized, featuring grand posturing with many stop-motion poses called mie. These mie poses are struck at moments of heightened tension and, like a picture or a sculpture they present to the audience in physical form a powerful crystallization of emotion. Another reason for this stylization in acting is that many of the most famous jidaimono were created as dramas for the puppet theatre (known today as Bunraku,) and they are performed with the same style of musical accompaniment that is heard in the puppet theatre. The music is called Takemoto, and it is usually performed by a shamisen player, and a narrator who tells the story and the circumstances, and describes the actions and emotions of the characters. In Kabuki, the role of the narrator is somewhat diminished, but even so, the subtle interaction between actors and musicians is key to the appreciation of classical jidaimono.Sewamono, on the other hand, portray in relatively realistic fashion the life of the ordinary people of the Edo Period, although plays in this category often show some stylization in presentation, especially at climactic moments.