A Rare Act to Follow

2/21/2016

By Paul Griffith

In the 4th month of 1795, two of the three major Kabuki theatres staged separate productions of the same play. The theatres were the Miyako-za and the Kiri-za, and the play was Kanadehon Chūshingura, ‘The Treasury of Loyal Retainers’. In the 5th month of that year, the third major Kabuki theatre, the Kawarasaki-za, also staged a production of this work. That all three principal Edo theatres should put on the same play concurrently was an unprecedented phenomenon, and points to the fact that there is something very special about this drama.

Chūshingura is arguably the most famous play in the Kabuki and Bunraku repertoires. Written for the puppets and first staged in the 8th month of 1748, it was adapted for Kabuki in the 12th month of that same year. Its authors were the three playwrights Takeda Izumo II, Miyoshi Shōraku and Namiki Senryū. The story of the 47 rōnin who avenged the death of their lord is often cited as an example of the samurai code of honour known as bushidō, but rather than this, it is the struggles and self-sacrifice of the individuals involved, so clearly and movingly portrayed in the play, that accounts for its enduring popularity. So popular was it during the Edo Period, in fact, that if any theatre suffered poor attendances it was believed that this play was sure to revive its fortunes. For this reason the work earned the nickname dokujintō, a kind of traditional Chinese medicine. In 1795, this seems to have applied to the Kiri-za because the Kabuki Nenpyō (‘Kabuki Chronology’) records that the performances in the spring were not successful, but that this production of Chūshingura was a big hit -「春以来不入の所、この「忠臣蔵」は大当たり大入。」

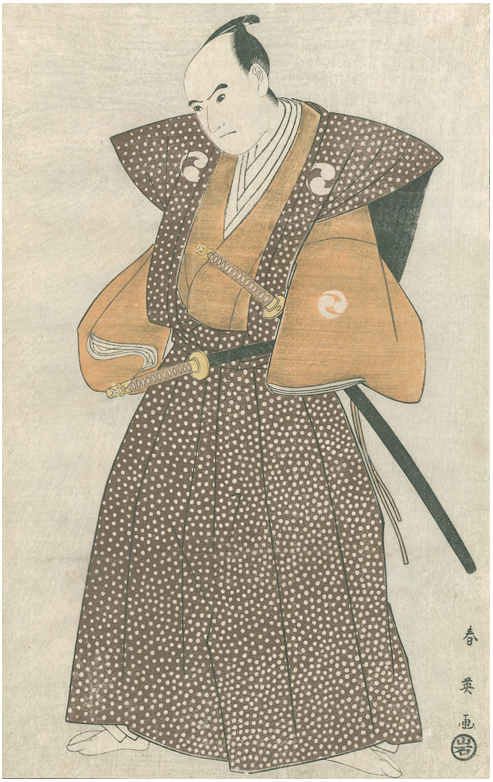

(left)Shun’ei – Sawamura Sōjūrō III as Enya Hangan in Act IV of Kanadehon Chūshingura, performed at the Miyako-za from the 4th month of 1795. (British Museum.)

(centre) Shun’ei – Nakamura Noshio II as Tonase in Act VIII of Kanadehon Chūshingura, performed at the Miyako-za from the 4th month of 1795. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

(right) Shun’ei – Sawamura Sōjūrō III as Ōboshi Yuranosuke in Act IV of Kanadehon Chūshingura, performed at the Miyako-za from the 4th month of 1795. (The Art of Japan.) (There is some doubt about the actor and role because records show that Yuranosuke was played by Bandō Hikosaburō III, and another design by Shun’ei also shows Hikosaburō in this role.)

Working with the publisher Iwatoya Kisaburō, the artist Katsukawa Shun’ei produced a set of at least 19 designs illustrating the plays at the Miyako-za and the Kiri-za. All are vertical ōban prints showing a single actor in role, depicted full-length, and the only inscription is the artist’s signature, “Shun’ei ga”. This is accompanied on most of the impressions by the publisher’s seal, the character ‘iwa’ (岩) within a circle. At the time the prints were issued, this lack of written information would not have been a problem for the majority of buyers: Kabuki fans would have known instantly all the actors and the characters portrayed and, probably, even the scenes and precise situations depicted. Today, this is not quite so easy to decipher, especially in cases where the scenes are rarely, if ever, performed.

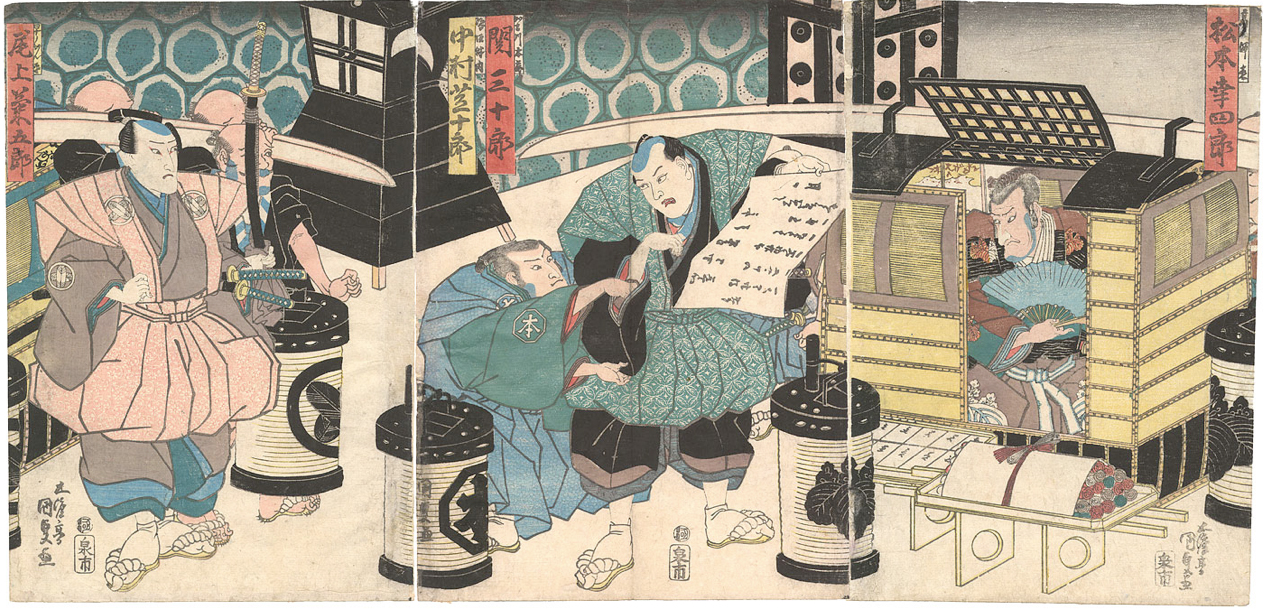

A case in point is the dynamic design illustrated at the masthead and to the right. Two vital bits of information are visible to the eye: the actor and the role. Since these are portraits, the facial characteristics clearly point to the actor Ichikawa Ebizō (Danjūrō V,) and Ebizō did indeed play three roles in the production of Chūshingura at the Kiri-za. Furthermore, the role is easily identified by the Japanese character ‘hon’ (本) seen just below the left elbow on the character’s black kimono. ‘Hon’ is the first character of the name ‘Honzō,’ referring to Kakogawa Honzō (加古川本蔵,) the chief retainer of the feudal lord, Momonoi Wakasanosuke. One of the three roles Ebizō played was indeed Honzō. But beyond this, the character is shown in an obviously heightened emotional state, so what scene is this from, and what is actually happening?

The play Kanadehon Chūshingura comprises eleven acts, out of which Honzō appears in three: Acts II, III and IX. His story, in fact, forms one of the moving subplots of the play. Moreover, his actions in Act III, scene 2, are crucial to the overall narrative because it is he who hides behind the standing screen when Kō no Moronō provokes Enya Hangan beyond endurance, and he who rushes out at the end of that scene to hold Hangan back from killing Moronō. In doing this, Honzō prevents Hangan from upholding his honour as a samurai, and therefore makes it necessary for Hangan’s rōnin to exact revenge on their lord’s behalf. In Act IX, Honzō atones for this terrible action by committing suicide in front of Hangan’s chief retainer, Ōboshi Yuranosuke.

But now time is pressing and Honzō must accomplish this before his lord departs for the Ashikaga Mansion early the next morning. At the end of Act II, after encouraging his lord to cut down Moronō just like slicing off a pine branch, he waits for Wakasanosuke to withdraw and then immediately orders that his horse be brought round. It is a moment of great urgency and tension, for he and a small group of fellow retainers must ride to Moronō’s mansion with all speed. In the words of the Takemoto narrator, “Shouting ‘Quickly, quickly!’ he at once tucks up the vents of his hakama and leaps from the veranda onto the horse that’s led into the garden.” (「早く早くと言う間もなく、股立しゃんとりりしげに、御庭に馬を引き出せば、縁よりひらりと打ち乗って」.) The hakama is the wide trouser-like bottom half of his costume, while the “vents” (momodachi) are the large slits at the sides. Perhaps it is a version of this action that we see in Shun’ei’s design, for the point is that Honzō requires greater freedom of movement to leap onto his horse. Tucking up the vents, or the ends of his kimono under his obi sash, he can gain this by freeing his legs.

As print collectors in the 21st century, we so often admire works by great artists of the past such as Shun’ei, and it’s easy to see the aesthetic value in what they’ve produced. But sometimes, especially in the case of yakusha-e, we fail to understand the whole picture. It is not until we know more of the subject-matter that we can experience the effect the artist intended, and finally get to grips with the true meaning of the design. Once we find this out, however, the work’s emotional impact is increased tenfold.